Part 3: The Role of Mindfulness in Adoption

Here is the last part of a 3 part interview that was originally published in Foster Focus magazine.

Get caught up with Part 1 on Adoption at the Movies (how to deal with adoption triggers online) and Part 2 on MileHighMamas (pre-adoption fears).

This interview, conducted by Addison Cooper of Adoption at the Movies, is of interest to anyone parenting via adoption of any sort — domestic, international, foster — or by donor sperm, egg or embryo. Our topic is mindfulness, which, as I talked about recently, is a supremely helpful tool for anyone parenting a child who has experienced a split between her biology (nature) and her biography (nurture).

Don’t Split the Baby!

Addison Cooper: You wrote that we honor the other parent’s role in adoption by not asking the child to choose or rank biology over biography or vice versa. People tend towards categorization and try to figure out where we fit in the pecking order of the world, what the different camps are in, for example, the “adoption triad.” That can hurt kids, though. How can we avoid doing that?

Lori Holden: You’re right that we categorize. And the adoption triad isn’t really a triad. For example, you and I are both in the adoption world, but you’re in the social worker corner and I’m in the adoptive parent corner, and other people are in other corners, like birth parents or adoptees or activists or therapists. Then we have other delineations: international or domestic, private or foster, happy or “angry.” We are always looking for differences and similarities and aligning ourselves accordingly.

The answer to your question of how to avoid hurting kids is pretty simple. We need to move from an Either/Or mindset — “either they’re your parents or we are;” “either you’re their son or you’re mine;” “you can claim either them or us” — we must move from that Either/Or mindset to a BothAnd heartset. The BothAnd approach acknowledges that “all of us contributed to who you are. They gave you something we can’t. We’re giving you something they couldn’t.”

When you have the BothAnd heartset, the Either/Or question is pointless. It’s splitting a baby, and who wants to split a baby?

One of My Favorites

What does it mean to you to be “one of” your son’s favorite moms, as you wrote?

On the morning of my son’s 9th birthday, I woke him up by gushing, “You’re my favorite son!” He responded with, “You’re my faav…errr…ummmm…you’re one of my favorite mommies!”

I was totally happy about that. If he had said You’re my favorite mom it could have been like splitting my baby. Did he feel he had to tell me that so that I would feel like the winner over his birth mother — at his expense? Would he be denying part of himself out of loyalty to me? I don’t want to cause him split loyalties from an Either/Or mindset. I want him to be free to claim BothAnd.

That’s beautiful. Would you describe parenting in seven words?

Rewarding and relentless practice of loving unconditionally.

Adoption’s Ghost Kingdom

You wrote about the “ghosts” of how things might have been. For birth parents, there’s the ghost child not being raised. For adoptive parents, there can be the ghost bio kid that never manifested. For adoptees, there’s the question of, what life would have been like with birth family or a different adoptive family. How can we deal mindfully with the ghosts of how things might have been?

The Ghost Kingdom is an idea from the late adoptee activist and psychologist Betty Jean Lifton, PhD. It’s really important to actually deal with any ghosts we have rather than pretend they’re not there, because “that which we resist persists.” Perhaps we all experience ghost lives, and it’s okay that we do it — as long as we do it mindfully.

I do sometimes catch myself with my own ghost child, the mini-me I had once dreamed of. I feel regret and even shame about that, but it would be worse if I tried to stuff it down and never deal with my thoughts and emotions. That would make it harder for my kids. It would make it harder for me. So I try to be mindful of my ghost child when she appears and say, “Oh, hi, there. I wonder why I’m conjuring you right now. What grief or loss do I need to process? Thank you for visiting, and now I’m returning to the kids I AM raising. Thank you for bringing me the gift of awareness.”

Being mindful is a way to neutralize our ghosts. Know that if you’re feeling wistful about the child you didn’t get to raise, it doesn’t mean you’re a bad parent, it just means that you’ve got a wounded spot that needs healing. Be gentle with yourself and be compassionate with your kids as they process their own grief and loss. Model for them how to deal with ghosts, for they may have their own pop up from time to time, too, of the lives they might have had and of the parents they aren’t being raised by.

The Importance of Grieving

It seems like the way we treat ourselves affects how our kids will treat themselves. This reminds me of the beginning scene of The Odd Life of Timothy Green. The couple is mourning the child that they haven’t been able to have, and they do that by imagining exactly what he would have been like. That always struck me as a healthy way of facing and processing grief.

In fact, one of the things our agency did for us during our pre-adoption training was to have each of us write a letter to the child we would never have. Maybe that shouldn’t be a one-time activity; maybe letter-writing can be a way to periodically deal with the ghost child that keeps popping up. Maybe you need to say goodbye again and again as new things come up for you through your actual child’s life.

You wrote that the less emotional distance or charge a child perceives between his two sets of parents, the more integrated his psyche can be. You also wrote that openness can help heal the split between a child’s biology and biography that is created by adoption. How can we help our children develop a healed and integrated psyche, and how does the distance between both sets of parents impact a child?

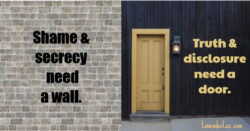

It varies as a child ages and goes through different stages, but through the long journey we trust the process. It’s a hard road sometimes, but it’s better to have openness than closedness (and by openness I mean more than just contact). Openness promotes mindfulness. When things are closed, when stuff is kept from us, we have a harder time being mindful and fully aware. You might try to keep things from yourself, thinking “Oh, I won’t deal with this and it will go away,” but things like this don’t go away when you don’t deal with them; they can grow and become even more unmanageable.

Minimizing emotional distance between adoptive and birth families can mean speaking about your counterparts only in a loving/accepting and never a derogatory way. It can mean choosing to love your counterparts simply because doing so is good for your child. In some ways, this is like a “good” divorce, in which the parents stay united in parenting even though they dissolve the marriage, versus a “bad” divorce, in which the children may become pawns of the adults who continue to have lots of unresolved triggers.

Doing Our Best

You acknowledge that adoption is complicated, no matter how you do it. Just because it’s complicated doesn’t mean you’re doing it wrong, and if you perceive it as uncomplicated, it probably means you’re not looking hard enough.

Heather Forbes of Beyond Consequences reinforces the concept that in parenting — even in mindful parenting — sometimes you don’t find immediate success in tough parenting situations. The best you can do in these moments is to trust the process and operate from your core, from a place of stillness and wisdom that you learn to use as a touchstone. In doing so, you stand the best chance to keep your own self regulated.

You said something beautiful and true in your book: that almost everybody is doing the best they can with what they have at any point in time. I see that there in Heather’s training, too. All we can hold ourselves accountable for is to do the best we can. If I plant a seed in a garden, I can’t be accountable for whether it grows, I can only be accountable for if I planted it well. If you become a parent, you can’t be accountable for whether your kid thrives or whether the relationships thrive, only whether you did the best you could do.

Exactly. We cannot control all the variables, but with mindfulness we can control ourselves. Being open, vulnerable, and honest with yourself and others, aiming for continual self-awareness – these are the ingredients that truly help us grow in our journey through adoptive parenting — and through life.

Giveaway

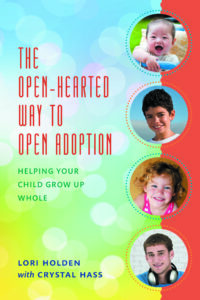

Did you enjoy this three-day interview series? Want even more insight into open adoption? Addison has three hardcover copies of my book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, to give away (cover price $29.95), one for each day of the interview. To enter, just:

- Sign up for Adoption at the Movies’ email list, AND/OR (and = double entry)

- Leave a comment below on how you would describe parenting in seven words.

Addison will pick all three winners at random on Saturday, April 11, 2015. He will notify the winner (make sure he can reach you) and arrange for shipping later this month.

~~~~~

See Also

- Part 1: What to Do When Triggered By the Online Adoption Community

- Part 2: Dealing with Common Fears about Openness in Adoption

- Brad Ewell stumbles into his own Ghost Kingdom

- Parenting GPS Series (also on mindfulness)

Lori Holden, mom of a young adult daughter and a young adult son, writes from Denver. She was honored as an Angel in Adoption® by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute.

Her first book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, makes a thoughtful anytime gift for the adoptive families in your life. Her second book, Standing Room Only: How to Be THAT Yoga Teacher is now available in paperback, and her third book, Adoption Unfiltered, is now available through your favorite bookseller!

Find Lori’s books on her Amazon Author page and catch episodes of Adoption: The Long View wherever you get your podcasts.

8 Responses

I love this: “We need to move from an Either/Or mindset.” I think that’s once again true even outside the adoption world. Especially as the child ages and moves into the larger world.

One thing I think is both helpful and dangerous is this idea of the letter. Because you’re imagining the child-not-here and romanticising that child. When we know that the reality is usually quite different from the child in our head. Or the dream spouse or the dream parent, etc. That real people can disappoint us and dream people can’t. So while it’s important to write that letter, I think it’s also important to acknowledge that the child or parent the person in the triad is imagining is not necessarily true to reality. And how do you reconcile the perfect, fault-free person in your mind with the reality you don’t know?

Exactly, and there’s the rub. The ghosts lacks dimension and substance, and are therefore perfect and unattainable. How could any real person go against that?

We have to recognize our ghosts AND value dimension and substance.

7: All consuming thrill ride of a life time

7 words: Learning to put others’ interests above mine.

Parenting is putting a child’s needs ahead of your own. By the way, thank you for featuring this interview. I have been entranced with Betty Jean Lifton’s concept of the “Ghost Kingdom” ever since 1979, when she published “Lost and Found.”

We are new to the world of open adoption and continuing to develop a relationship with our two-month-old daughter’s birthmother. We also have two bio sons. Parenting is, “Giving sacrificially, a rewarding responsibility, love-filled.” Thanks for this information!

7 words to describe parenting- can’t wait to try it out already

❤ Amber.