virtual book tour

Read With Me: The Novel “Perfect Little World”

Infinite Family Project Kevin Wilson’s Perfect Little World came to my attention when Melissa Ford wrote about it. I’ve long enjoyed discussing books with Melissa

Infinite Family Project Kevin Wilson’s Perfect Little World came to my attention when Melissa Ford wrote about it. I’ve long enjoyed discussing books with Melissa

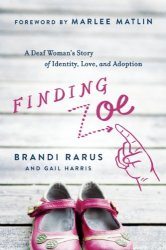

What was the social worker’s take on this story? What is the relationship like between birth mom and birth dad today? How did you decide

But what about supporting the birth father when he indicates an interest in parenting? Why didn’t we hear from the social worker involved? What about