That sounds really mean, doesn’t it? Hear me out as I make that case that sometimes you gotta be cruel to be kind.

“Children Are Anti-Fragile”

In a broader discussion of what he calls the vindictive attack culture on college campuses, Dr. Jonathan Haidt, a psychologist and professor of business ethics at New York University’s Stern School of Business, says:

A carton of eggs is fragile, if you bang it around it breaks. But bone is anti-fragile. If you bang it around it gets stronger, and if you don’t bang it around it gets weaker. Children are anti-fragile. They have to have many, many experiences of failure, fear, and being challenged. Then they have to figure out ways to get themselves through it. [bold added by me]

I’ve been thinking about this in terms of parenting, adoptive parenting and modern culture.

Anti-Fragility in Adoption

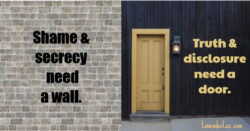

Parents can misguidedly overprotect their children when it comes to the hard stuff in adoption. I recently spoke with a friend who donated her remaining embryos to another family in what was to be an open adoption. However, because it might be too hard for the now 7 year-old to process his story and to know his genetic siblings (which was important to my friend and her husband), the parents have decided not to tell him, not to have contact after all.

Never mind how much this decision hurts my friend, but what about the effect on the boy? I fear the fragile approach will not work out well for him. Our job as parents is not to protect our kids from all difficulties, but to teach them to handle difficulties, to uphold that they can handle challenges, and to walk alongside them as they experience both successes and failures. This I would call an anti-fragile approach.

Do I want my kids to struggle with their adoptedness? Of course not. But if there is to be a struggle (many of you tell us there inevitably is), do I want to be there to support them, to cheer them on, to have them allow me in to their struggles? Of course I do.

(By the way, children aren’t the only ones who are anti-fragile, Remember the images of Astronaut Scott Kelly returning to earth? Without the stress of gravity for nearly a year, his veins, muscles, and bones weakened to the point that he had to be carried off the spacecraft.)

The Rise of the Coddling Culture

Dr. Haidt says in The Revenge of the Coddled that the coddling culture arose in the 1980s, which means for awhile now we’ve been feeling the effects on college campuses.

The great majority of people over 35 seem to dislike this coddling culture, they were not raised with it. Most of them had “free-range” childhoods where they spent time without adult supervision and were expected to fend for themselves. So the biggest divide is age.

The Atlantic’s The Coddling of the American Mind mentions the rise in use of the terms “microaggressions” and “trigger warnings” at colleges and universities in an effort to “turn campuses into ‘safe spaces’ where young adults are shielded from words and ideas that make some uncomfortable.”

How did we get here, to the place in which young adults demand to be treated as though they’re fragile? The Atlantic article follows many threads and theories. In addition to those, I notice these differences from my own memory:

- We now call bullying what we once called being mean.

- We now consider inexcusable what we once considered ignorant. For example, have you always steered clear of all these words? (I see a few I’ve used* — because I just didn’t know.)

- We now report bullying and inexcusable behavior (formerly known as meanness and ignorance) to a higher authority, and/or vent on social media about the same things we were once told to toughen up for.

BothAnd of the Serenity Prayer:

Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

Back then, the thesis seemed to be: here’s the world. It ain’t gonna change for you so you must change for it. You gotta figure things out, You gotta toughen up.

Sure, there’s something to be said for accepting the things we cannot change. Yet I see why that’s not a perfect philosophy because sometimes, the world does need changing. A new stance, an antithesis to the one before it, can be an empowering one: if you don’t like the world the way it is, make it better.

But maybe the pendulum has swung too far the other way as we focused too much on changing the things that can be changed. And in our zeal, perhaps we sacrificed acceptance in favor of change.

And now it’s time to modulate, to find synthesis, to seek both the peace to accept (“toughen up”) and the courage to change (“make things better”). It’s not an either/or choice; turns out we need both strategies, as well as the discernment to tell which approach to take and when.

To cap things off, as I’ve been pondering anti-fragility all week, my yoga teacher quoted an unknown person recently. So yeah, I think it’s okay — even necessary — that my anti-fragile kids struggle. For in their struggle they find their strength.

* Gaijin and Canuck, for example. Is it OK to type these here?

Lori Holden, mom of a young adult daughter and a young adult son, writes from Denver. She was honored as an Angel in Adoption® by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute.

Her first book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, makes a thoughtful anytime gift for the adoptive families in your life. Her second book, Standing Room Only: How to Be THAT Yoga Teacher is now available in paperback, and her third book, Adoption Unfiltered, is now available through your favorite bookseller!

Find Lori’s books on her Amazon Author page and catch episodes of Adoption: The Long View wherever you get your podcasts.

21 Responses

Your post makes me think of how essential struggle is to emerging butterflies. In the absence of this effort, their wings lack the strength to support flight.

I agree that it is through the survival and conquest of challenges that children increase their skills, confidence and ability. The grace lies in knowing when to cheer from the sidelines, when to offer help and when to hold back and allow events to unfold, “failure” to occur and lessons learned. Great post!

Totally agree that it’s better to help them handle vs. protect in the same vein as the “teach a man to fish” argument: We won’t be around forever (and can’t be with them 24/7), so better to know how to get through difficult moments rather than only know how to steer around them.

I think the only difficulty lies in the people who don’t actually teach the handling part. I don’t think our “free range” childhood would technically be considered “free range” by today’s free range movement. I was taught and guided by adults a lot while running around outside. And in speaking to “free range” parents today, they seem to be taking the ideology as the opposite of hovering and making it hands off. Which sounds like the kid ends up doing the hard work of teaching herself vs. and the adult gets to claim they’re giving their kid a “free range” childhood while not using their energy/time. I think parents today don’t realize how much work happened behind the scenes in order to give us that “free range” experience. That there was a lot of supervision that we didn’t know about at the time, and that supervision created a feeling of comfort so we could explore the world. But just sending out your kid to play without that network and teaching moments in effect is just as detrimental as the coddling.

So then it becomes, how do we build those networks that existed during our childhoods so our kids can learn through error and be guided through experiences vs. left to grapple on their own?

Such a great point, that allowing children to face their struggles doesn’t mean abdicating from parenting. On the contrary, as you say, t means having structures in place to make sure the struggle stays manageable, and also remaining nurturing. There is an ongoing dance that includes both structure and nurture.

I think it takes MORE work in that case. That free range parenting ends up being more hands on than helicopter parenting, just in a different way. I mean, when it’s actually parenting and not just the absense of parenting and calling it parenting.

This is SUCH a good point. Growing up in Hong Kong I was allowed to do insane things as a sixth grader, but I know my parents let me do them because they had worked hard to teach me the skills needed to do them compentently. I absolutely consider myself a free range parent and hope to give my kids a lot of freedom in the city where we live when the time is right. I’m already laying that foundation now, by letting them swipe their own cards when they get on adn off buses, by making point out which adults work at the subway and talk to them, and requiring they ask adults for things when they need them. We practice walking up to someone at the zoo and saying we’re lost and giving our information. It takes a lot of time and forthought. It’s intentional and deliberate. It’s not about just not keeping at eye on them at the park in the zoo, it’s about giving them the freedom to play without me shadowing them (the older one at least) and letting her see that she can find me when she needs me (or ask for help when she can’t).

“Do I want my kids to struggle with their adoptedness? Of course not. But if there is to be a struggle (many of you tell you there inevitably is), do I want to be there to support them, to cheer them on, to have them allow me in to their struggles? Of course I do.”

YES

I really wish more parents were like you in raising the next generation. The only way we learn is by struggling and getting through it. Life is never easy we are just able to get through it by becoming stronger.

Just like with Yoga you may struggle some days or in getting into certain poses but by challenging yourself eventually you’ll be able to get where you want to be. 🙂

I LOVE this post. Thank you so much for reading it. Recognizing that my kids are “anti-fragile” and that they need disappointments to become stronger is a HUGE part of my parenting. I was just having a conversation with my husband the other day about this, when my daughter didn’t want to eat the pizza at a party to get her cupcake. My husband wanted to just let her have the cupcake, but I could tell she could handle the hard work of deciding if she was going to eat the pizza to get the cupcake right then or wait and bring the cupcake home to have after a different dinner. She had to go into the stair well melt down and we had talked about it, and she ended up going in and taking five bites of pizza and getting her cupcake. And when I asked her if she was happy with her choice, she was and seemed really proud. It’s hard work and requires a lot of consistent parenting, but letting our kids make hard choices and learn from their mistakes is SO important. I see parents trying to protect their kids from disappointment or hurt all the time, and it’s so frustrating, because middle school is the perfect time to learn that not doing your work negatively affects your grade–don’t make them wait until high school to learn that! I wish more parents were like you. I really do worry about the next generation, and what they’ll be able to handle. Adulting is going to be TOUGH for them. 😉

I struggle with this at work (at my university) where — believe it or not — it is my role to protect students from failure. They fail in smaller ways, and we talk them through those failures, but the spectacular failures rarely happen. I don’t always think this is the best for them.

We have a lot of conversations about microaggressions; I think part of the problem is that children aren’t taught to be civil, and so they come to college not only with hurtful words, but the inability to imagine why they might want to be thoughtful, and on the other hand, how they can respond in ways that are productive. Another part of the problem is that our generation has tended to dismiss the reality of racism, classism, and sexism that still exists, so many students come to the table assuming that it’s all equal, but then make assumptions based on the bias they’ve been taught (implicitly, in most cases). Perhaps some of them are so self-centered (because of the helicopters) that they’ve never really had to care for or about others, so one problem actually begets or recreates the other?

In any case, it’s a thorny thing to deal with once they’re here, they’ve been parented (or not), and now we’re acting in loco parentis.

This is an interesting point. There’s data that shows this current generation of young adults either was overprotected or not protected at all. With overprotection, one could image not having exposure to racism, sexism and classism, but on the flip I wonder if there’s also been sheltering from the consequences of such actions. That they have not been properly taught empathy.

It’s hard to watch anyone fail. As teachers, we do try to guide and protect them as best we can. But sometimes it is a good thing. Being made uncomfortable or having your ideas challenged can lead to reexamination.

Lori: Once again you’ve hit open a cultural nerve and have sparked a valuable exchange of ideas. I agree that as parents we must strike a balance between extreme free range parenting a la “Lord of the Flies” and helicopter parenting which indoctrinates kids to have a helpless self image–one that needs constant rescue and assistance. As parents we best serve our kids when we nudge them along to independence with incremental steps of increasing challenges that lead to mastery, capability and confidence and courage.

OMG, yes!!!!!! One of the hardest things I struggle with with my students (ages 20-22 yrs old) is failure. There has been such a push to protect them at all costs from failure that when they finally encounter it as adults, the response is either completely shutting down, aggression bordering on violence and even suicide. Helicopter parenting has created a generation that lacks the stills to confront and overcome failure. It’s tragic on so many levels.

Pain, anger and frustration are amazing teachers. Through them we learn limitations, change behavior patterns and find motivation to try new things. It also embeds a clear understanding of what not to do. The story of your friend saddens me because the adoptive parents are setting up a huge potential for pain given they are withholding information. Unintentionally, they are teaching their son that they can’t be trusted and creating a culture of secrecy all in the name of protection.

But in addition, learning to deal with pain and failure teaches one how to respond and overcome. Yes, we need to protect our kids, but not cocoon them.

Beautiful post Lori.

I love, love, love this post! Especially this: ” Our job as parents is not to protect our kids from all difficulties, but to teach them to handle difficulties, to uphold that they can handle challenges, and to walk alongside them as they experience both successes and failures.” There’s a resiliency that’s missing in kids who are taught that failure is bad, that they must be protected from everything, that mommy and daddy will take care of all the painful things and protect/defend you from the world. I see it as a middle school teacher for sure. I worry about being a bubble parent myself one day, wanting to protect my child from unpleasantness, but I guess seeing as how I was raised “free range” and life is FULL Of unpleasantness, I think I’ll be okay helping my kid navigate the unpleasantness and build up their coping strategies and toolbox for dealing with the crap life throws at you. What an amazing gift to give a child, adopted or not. Thank you so much for this post!

It makes me crazy that my daughter fears failure so much – she doesn’t even want to try sometimes because she’s not an instant expert. Then I end up forcing the issue. Sigh…

I think she is getting that practice makes perfect. And some issues that she’s having at school motivate her to try different things.

I think your pendulum analogy is apt. I’d say, there’s a balance, and we’ve yet to find it. Remember a few years ago when a boy was legitimately bullied because he brought a My Little Pony backpack to school? The Internet took sides – that the boy should learn to toughen up because he wasn’t a special snowflake or that the bullies should be punished and schools should stop steeping our kids in gender stereotypes.

I see that happening a lot with really any typical childhood situation. Now, I’m in the schools need to stop with the gender stereotypes camp. No kid should be bullied, or even teased to the point of tears, for his choice in backpack, clothes, lunchbox, etc. At the same time, parents need to empower their kids. Teach them how to handle such situations, whether they’re the target or simply a bystander.

Anyway, I’ve strayed from the point of adoption. All of your adoption advice was, as usual, on point. I’ll pin this one to come back to and quote sometimes, I’m sure.

Love it. Brilliant and insightful and mirrors my concerns/patenting approach.

My daughter had a cat that was quite ill and had to be put down, she was 6.5 yo at the time. My husband wanted to know if we should tell her the truth or make up some story about how the cat had been taken elsewhere and was fine. I told him the truth was always better, and that she needed to learn that things die. Bad things happen and you have to learn how to handle them. Besides which, keeping up the fiction he suggested was not viable anyway, sooner or later she’d want to see the cat again.

I think it is natural to want to protect the ones you love from bad experiences, but there needs to be a sense of perspective and a long term view. You have to think about what they will need to deal with as an adult and build the foundations when they are young.

We were just discussing this at my local writers’ group. Hubby and I are firmly on the non-coddling side, and not just with our own kids. I completely agree that while it’s not always (or ever) easy, the struggle is necessary and totally worth it.

Interesting. I would add a synthesis of your points: that creating real change in the world requires “toughening up.” Facing up to ones failures and shortcomings is also a crash course in the limitations of people in general, since we share the same flaws, though they are expressed differently depending on personality, culture and experience. Before trying to change the world it is important to consider what can be changed external to us and what must be wrestled with internally: the moral conflicts, on other words. Both take great courage and neither struggle is meaningful without the other.

Without first “toughening up” in this way, I’m afraid “changing the world” becomes like that deeply awful Google commercial where people are shown googling “how do we make world peace” and similar tosh while major key music plays. I’ve spent a lot of hours googling, and I can bloody well assure that never changed the world.

I’m so glad you brought up the compassion angle. Yes! Needing grace once in awhile helps us understand why it’s important to also extend it to others.

You know I am totally with you on this, Lori. 😉 And I love Jess’s point that this applies whether you’re adopted or not. I adore our two nephews (now in their 20s) but they have lived at home all their lives & been totally coddled/spoiled, and their parents fret endlessly about every little difficulty they encounter in life. Oldest nephew (27) only JUST started paying for his own gas for his car!! & their parents still pay for their cellphones (although if they want data, they have to finance that themselves). And then the parents wonder why the kids have no money sense. 😉