How do I tell my child he’s adopted? And when?

Note: I’m frustrated that these questions still come up (and surprised because my readers are adoption-savvy, so I start thinking everyone is). Who is preparing adoptive parents for adoption telling? And who should be preparing them? What can we do for the current and next generation of adoptees to help them own their story from their very beginning?

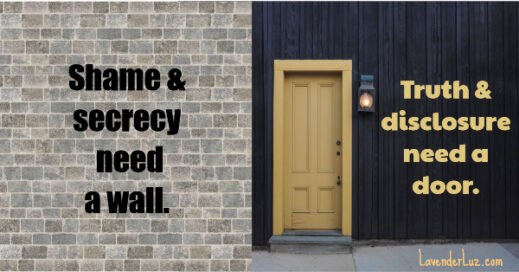

The move toward openness in adoption started in the 1980s, which means for more than 40 years we have been morphing from shame, secrecy, and walls of closed adoption => to => truth, disclosure, and doors of open adoption.

But time alone doesn’t mean all adoptive parents and hopeful adoptive parents have gotten the message of dealing in truth and openness. The adoption professionals who are launching these moms and dads into the world of adoptive parenting are not, as a group, doing a good-enough job preparing their paying clients to parent with openness and disclosure (there are definitely some exceptions).

Prospective parents, though, may bear the ultimate responsibility for learning about current best practices in adoptive parenting. But how can they know what they don’t know? A blind spot is, by definition, a thing you can’t see is there.

Recurring Evidence that Parents Don’t Know When & How to Disclose

A few times a month, someone will ask in a social media adoption group WHEN is the best time to tell their child they were adopted. And WHEN to disclose information about that child’s birth family. We’re not talking about an advanced course in “open adoption” — facilitating actual contact — but merely the basic disclosure that the child’s origin story has an extra element in it: adoption. That the child has first parents.

And that we can talk about it all.

Why Can’t Parents Talk About Adoption?

Time and time again, I hear this from well-meaning parents: We’re waiting until our child is ready to hear.

What I hear behind the words, though, is this: We’re waiting until we’re ready to tell.

But becoming ready doesn’t necessarily happen automatically, which creates a big problem for the whole family, not least of all the adoptive parents.

Sorites: A Paradox

Relevant here is the concept of sorites, a term I learned a few years ago from a New York Times‘ Ethicist column headlined “Should a Sibling Be Told She’s Adopted?”

‘Sorites’ (saw- RAHY-teez)’ — from the Greek for ‘‘heap’’ — is the name of a philosophical paradox. A grain of sand isn’t a heap, and adding one more grain can’t make it a heap, and as you add grains of sand, you reason that another grain can’t turn your pile into a heap. Yet at some point, a heap is what you have. In the temporal realm, there’s an analogous problem. Very often, it won’t do any harm to wait one more day to do something. So you put the deed off until, at some point, you’ve waited too long.

Sorites sins can creep up on well-intentioned people. Maybe your wife meant to tell you, when you first started dating, that she once had a fling with your brother, but the time never seemed right. There was no particular moment when she crossed the line from permissible deferral to culpable silence. A decade later, though, a spiny eel wriggles in her stomach whenever she thinks about it. She prays you never find out.

Sorites sins can rock relationships.

— Kwame Anthony Appiah, NYT Ethicist columnist in 2016

The Effect of Not Telling

Never mind the causes of why some parents can’t (or won’t) talk about adoption. They are numerous, individualized, and because they are in the past, they can’t be changed.

But the effects can be known and mitigated. And this leads to a deeper point than merely figuring out when and how to tell:

Whatever is keeping adoptive parents from telling is probably hindering their ability to parent effectively in other ways.

Because when parents are not disclosing something so big and integral to a child, they are not able to build a fully trusting relationship with him/her. Lies of commission and omission are likely to be devastating to the person they are about, once they realize that parents knew and did not/could not tell.

Not being able/willing to tell can also mean parents are having a difficult time dealing in What Is, in accepting the whole story of how the child came into the family, of the existence and validity of another set of parents — all in an effort to keep their own fears and insecurities at bay. If there is denial going on in one place, there may be denial going on in others (see the 1956 study listed in Resources, below). This compromises the ability to be truthful, which hinders the ability to build trust.

Adoption Telling is in the Best Interest of Parents!

When children sense they cannot trust their parents, they are more susceptible to looking for connection elsewhere. This can manifest in so many nightmarish ways, and as you can imagine can lead to lots of problems for the child and parents.

As I’ve said before, as the tween/teen years approach, parents are going to want to have a clear and trusting channel of communication between them and their adolescent. There really is no other true power in parenting during this stage. Grounding and withholding things can only go so far. Trust and connection are vital for making it through the turbulent tween/teen years in a trusting and connected way (adoptive parents: if you’re not already in this Facebook group, consider joining).

As one wise and experienced parent said in an online group, disclosing early and fully is “so much EASIER. No big reveal, no nervousness, no confusion, no sense of betrayal, no lies. Just the truth.”

What do you think? How should adopting parents find out best practices, and who should be tasked to make sure they do? With a focus on a solution (and not just on placing blame), please offer your ideas for progress for better adoption telling in the comments.

Relevant Resources

- Should a Sibling Be Told She’s Adopted? — New York Times Ethicist

- When to Tell a Child They’re Adopted: “Trust is a fundamental part of your relationship with your son, upon which everything else rests. So you must tell, and soon. If you have a series of little talks, you won’t have to have The Big Talk.”

- 9 Steps to Long-term Success in Adoptive Parenting: free webinar (the 4th one down)

- Delaying Adoption Disclosure: A Survey of Late Discovery Adoptees — research study by Amanda L Baden, PhD

- A 1956(!) study that shows parents should “inform the child early” and that “adoptive parents reveal important attitudes on acceptance of adoption in discussions about telling the child.” (truth as a best practice has been around for at least 60+ years!)

Thanks to TAO for those last two.

Lori Holden, mom of a young adult daughter and a young adult son, writes from Denver. She was honored as an Angel in Adoption® by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute.

Her first book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, makes a thoughtful anytime gift for the adoptive families in your life. Her second book, Standing Room Only: How to Be THAT Yoga Teacher is now available in paperback, and her third book, Adoption Unfiltered, is now available through your favorite bookseller!

Find Lori’s books on her Amazon Author page and catch episodes of Adoption: The Long View wherever you get your podcasts.

35 Responses

So well described and so necessary.

Thanks, Gayle. I’d love to know if you have ideas for how we can remedy this.

Cheers, one of my pet peeves is AP’s not telling.

One quibble with your first paragraph, the vast majority of AP’s pre-80’s adoption told, so while some chose external secrecy, telling happened.

Thanks for the shout-out.

Point taken. What do you think made the difference between those who told easily and those who weren’t able to?

I think it comes down to acceptance of what is after infertility. Mom and dad were both realists and grew up during the depression when you just had to accept what is as a daily reality. They wanted biological children, no doubt there and grief was there was well, but not in how they lived, no time for that, they also knew why babies weren’t coming so that may have helped having a reason.

Hard to describe but I truly think parents from my era had it easier because there were no magic wands, cures, or options like today to make people keep their hopes up, endlessly. I do think those options and the never-ending losses do play a role.

I love that you bring up acceptance of What Is. My own teachers call it Radical Acceptance. It’s so hard, but also it seems to be the answer to so many of my problems.

There should never be a day you learn; it should simply be part of your story, even before you understand your story. But I do think it needs to be part of parenting training. That parents need to hear that and understand why. Have that knowledge be part of the adoption process so adoptive parents have the tools to be the best parents they can be.

Excellent point. I’ve heard it said that the child should never remember having The Talk.

Completely agree with this.

Such a great post, so informative and well-researched, but also with your trademark empathy and break-it-down-ness (? that makes sense, right?). I enjoy how you make that distinction of “when they’re ready to hear” vs “when I’m ready to tell.” I think that comes up in a lot of difficult conversations that people do not want to have — I loved that sorites piece. I agree that adoption should just be part of the story, from the beginning, no Big Talk. I was not successful, but I have friends who were, and it’s wonderful to see that everyone is going with transparent, open, honest communication with their children, no matter how young. You make such a great point that in in the tween/adolescence swamps, open trusting relationships are so key, and this lays the foundation.

Because you’re someone who works with adolescents and builds trusting relationships with them, your validation means a lot!

My wife used to say that I was ‘raised by wolves’. By the time I discovered just how true this was, most of the wolves were dead. The remaining wolves were cut from my life and have since died. The totality of my reaction to them is to be thankful they are gone. This may not be a universal reaction by late-discoverers, but it is also not unusual.

Their issues harmed me and they reached through me to harm others.

Broken trust is just so hard to get over. If people could foresee this, they might make different decisions.

Thank you for sharing your insight, painful as it was for that to have been your story.

“Sorites” is my best new word and concept for 2020, and we’re not even halfway through January. Thank you!

When we were taking adoption prep classes in the ’80s, we heard presentations by experienced adoptive parents and by birthmothers, but I don’t remember hearing from adult adoptees. Maybe that would help reinforce the concept that adopted kids grow up, and the conversations we did or didn’t have will be part of their reality forever.

I also wonder if there is a way to generalize post adoption education and support. If I were in charge and had magic powers, every new adoptive family would get a notification once or twice a year with links to age appropriate resources about “telling” and other inevitable issues/opportunities. Everyone would have access to an adult adoptee mentor they could turn to for advice. You shouldn’t and can’t force people to parent any particular way, but maybe having resources — and that periodic nudge from the world outside your own household — would break down the sorites heap before it becomes a mountain.

I see Camps incorporating adoptee voices, but not so much agencies. The ones who do are on the right track for the reason you say.

I love your idea of a standard of care for adoptive families that would include sending resources over the years.

I’m glad you like “sorites.” It explains the grain/heap paradox so well.

Great comment, Bluepoint.

I continue to think that this discussion is (much) too gentle.

Consider this: https://medium.com/@mirahmirah/when-adults-discover-they-were-adopted-be60c4a242ad

Read some of this: https://www.latediscoveryadoptees.com

:

I remember when that Medium article came out. Not only is a person’s trust in parents shattered, too often their ability to trust AT ALL is vaporized.

Mike –I remember following Ron Morgan’s saga on Bastard Nation groups in the ’90s. Among other things it made me appreciate that the visibilty of our transracial adoptions meant that not telling wasn’t an option. We all like think we’d do the right thing anyway, but….

Thank you for continuing to speak up.

“Time and time again, I hear this from well-meaning parents: We’re waiting until our child is ready to hear.

What I hear behind the words, though, is this: We’re waiting until we’re ready to tell.”

This. As a mom to two kids who were conceived by donor eggs, I can so relate to this. Adoption and third party reproduction have a lot of parallels in disclosing their origins. Thank you for putting this out there.

So true about those commonalities. Make sure to click on that webinar I linked to, as it was hosted by an organization that promotes openness with donor embryos.

No one should be able to pass a homestudy without learning how to tell a child’s adoption story early and often. The homestudy is the one common denominator for all adoptions – domestic or international, public or private. Even kinship adoptions often require homestudies. Make it the responsibility of the homestudy agency or social worker to educate HAPs. Include a contract of sorts that includes a written promise to tell the child his/her story from day one. It might not be legally binding, but it would certainly emphasize the importance of honesty.

Love this idea. Along with Bluepoint’s ideas on resources, I want to start thinking how to make a homestudy requirement like this more standardized across the country.

Thank you, Robyn!

Our nieces were adopted from China, so it would have been hard to conceal that. My cousin was adopted as an infant, and it wasn’t a secret per se (I knew from about age…7 maybe? And he’s a couple years younger than me.), it was not really discussed either. Apparently, he had some strong feelings about it as a teenager, but since they lived 100+ miles away, I only heard second-hand. He’s a seemingly well-adjusted adult with a nice family now, but never had any interest in finding his first parents. I assume at some point, his kids will do the 23 and Me testing and open up a whole history that he never wanted to address.

But every family has issues that they think they need to hide. Adoption is no different than…what my mom used to describe as the breakdown that Aunt Lorraine would have every year when school let out (and I think she had only one child, who is the mildest human I know). Families are weird and difficult and fascinating and important. Share everything.

“But every family has issues that they think they need to hide. Adoption is no different”

The difference is that I AM that secret and the secret is being kept even from me. So you are taking my self, my identity, my emotional uniqueness and putting it is a box to be hidden in the attic. You are rejecting it, you are rejecting me, and you are even keeping this fact from me.

If I am your issue to be kept hidden, what does that say about love, support, acceptance, nurturing? Those things that ought to be part of ‘family’ but never make it to the cage in the attic where I am kept?

Eventually, I will no longer be your issue and you will no longer be my prison guard. By then it will be difficult for me to learn what family means to other people but at least I can try and at least I will know why I have this deficiency. Family will never be an integral part of me that I can give to others.

I’m not trying to pick on the poster, A, specifically. I’m trying to make a point. It is difficult for me to be party to a polite conversation that treats a decision to hide a person from themselves as if it could ever be moral or excusable.

Did you read beyond those phrases? People have hidden mentally ill relatives or relatives who have divorced or other people with “unacceptable” traits, and it never works out. I’m certainly not advocating hiding. That’s why my last sentence was “Share everything.”

We are learning, as a society, that many things previously considered shameful are really just a part of life. Experiences of adoption, mental illness, homosexuality, other non-conformities, are now known to be better shared so as to lessen the burdens.

you rock. tell her

Such an important piece. And I love the comment at the very end from a parent in one of your online groups: Just the truth. YES YES YES YES.

It just occurred to me that when you factor out transracial adoptions, and older child adoptions — both stepparent and nonrelated — probably full-scale secrecy isn’t even an option most of the time. Same-race infant adoptions are much less common than they used to be. So the people who even have the option to struggle about “when to tell” are kind of living in a bubble. Most of us don’t have that choice.

Still there’s a big difference between having “the talk” just once and being open about adoption discussions.

This is so good! I love the point about parents not being ready to tell. What I can’t understand is why parents, who wanted children so desperately that they used donor egg or adopted, then don’t think about what is in the children’s best interests, but do what is easiest for them. I heard on a British TV programme recently that donor sperm in the UK is more frequently sought from another country (I can’t remember which) than from the UK, because the other country allows anonymous donation. That made me so mad!

Also – sorites. Brilliant. I am guilty of one or two (minor) sorite sins I think!

All of this echoes deeply with me. My nephew is a young adult and though he knows he was adopted (first family’s parental rights were terminated when he was 5 years old), no one has ever really talked with him about his story and given him a foundation to process all of this. And it shows because this is a young man who is hurting on so many levels, with parents and relatives who insist that they don’t need to talk about any of this stuff while being baffled why he’s struggling so much. And they get insanely angry with me for pointing out the elephant in the room.

It’s more than opening the door once. It needs to be an ongoing conversation built on a foundation of trust where all parties know they can communicate. The alternative is generations of hurt and dysfunction.

So much wisdom in your post and in the comments! My guess is parents don’t tell because, deep down, they don’t want to be reminded that they’re not, in fact, the child’s first parents. I also think that you’re right about the need to reinforce the importance of honesty right from the outset in any training/education/counselling the adopting parents receive. You & your readers are all very well read & have thought about these issues a lot… unfortunately, that’s not always the norm. Many of the bereaved parents we dealt with in our pregnancy loss support group also had fertility issues, and I was shocked by how little some of them knew about the whole subject. The assumptions, the misuse of terminology… Researching the hell out of what I was up against was one of my coping mechanisms… I had to remind myself that not everyone was like me and did that for themselves. 😉

Excuse my while my head explodes……

1. I’d like to see adoption agencies best practices. It seems that starting with education around the “when to tell”, which in our case we were told “start practicing when they can’t even talk so that you get comfortable with telling the story by the time they can understand you”. I like that approach.

2. I ran into this issue last summer at Adoption Heritage Camp of all places. This very question, “When should we tell our kids they’re adopted?” (the kids were 3). Pretty sure I just stared at the parent in disbelief.

3. IMO now that I’m all awake and aware and stuff…self-mastery is where it’s at. When we can’t get ourselves out of the way in order to parent, that’s where all the trouble starts. Not just in this realm, but all realms of parenting.

I’ll get off my soapbox now.

Even though adoption is marketed as a positive thing, deep down most people know that it’s not. There is shame. Shame that a woman got pregnant without resources to keep her child. Shame that another woman can’t bear children. Shame that a baby was given away. Shame that money changed hands.

Some people would rather hide than face all of that. Still, even today.

In my world, growing up it was, it’s nothing to be ashamed of, but don’t tell anyone.

Isn’t that a confusing mixed message, Marylee?

I agree with you that it’s weird something packaged as so positive was also something to not speak of. A helpful observation.

“Even though adoption is marketed as a positive thing, deep down most people know that it’s not. There is shame …”

Hmmm. My take is that adoption is a complicated thing. Complicated things are, well, complicated, and they can be hard to think through and hard to talk about. That’s one reason resources like this site are so important.

None of us — original or adoptive parents — can be good models or advocates for our kids if we are silenced by shame. And some adoption attitudes and practices have been and still are shameful. That’s another complication.