It’s Adoptee Month at LavenderLuz.com. In honor of National Adoption Awareness Month, spend November reading a variety of adoptee voices here. All essayists have responded to this prompt: what I wish adoptive parents knew about parenting an adoptee.

Today’s voice belongs to Cynthia Landesberg.

The Green Binder

My adoption file lived on the top shelf of my mother’s closet in a forest green marbled binder. My mother pulled it down every now and then to show me the two pictures she had of me from Korea, but she never invited me to look at it or left it out for me to flip through. Instead, she always returned it back to its place tucked between old photo albums and insurance papers, my history firmly out of my reach.

As I grew into a teenager, home alone after school, I would sometimes sneak into my parent’s room to look at that binder. I would drag a tall wooden chair to the closet, watching the carpet fibers fold in streaks of dark blue behind me, marks of my misdeed that I would wipe clean on my return trip. I would climb on top of the chair, teeter on my tiptoes, and snag the binder with my fingertips. And then, crouched on the chair, I would guiltily skim the pages, brushing my fingers along the typewritten letters in Korean and English, and hungrily rifle through my past.

Just Three Sentences

My parents told me the same three-sentence story about my birth family every time I asked.

“There’s not much to know. Your birth mother left you at a police box in Busan, wrapped in a blanket with your name and your birth date written on a note. She wanted you to be found and adopted.”

I built a shelter out of these beliefs. My face, my name, and my birth mother’s selfless wish for me formed the walls of my identity, a trifecta under which I could find solace in my strange existence as a Korean in a Jewish White family. I would sit in my room and write my Korean name over and over, imagining I was her writing my name for the last time, trying to extract the hidden message of love I felt sure was there.

And then, some thirty years later, I asked to receive an electronic copy of my adoption file from the adoption agency because my parent’s copy remained sequestered on the top shelf of the closet. Now, no longer a child guiltily grasping at hidden history, I took time to review the paperwork with care, and what I found left me confused and hurt. I learned that the story my parents told me did not match the one the adoption agency gave them. The paperwork actually said I was found on a street by a stranger rather than at a police station and that my Korean name was given to me by a social worker rather than my birth mother.

Counterfeit Gems

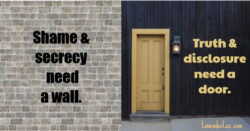

You may be thinking these are small details, but with so little of my own history, these details were everything. I clung to them as precious gems, assurances that my birth mother wanted this life for me and that she gave me a part of her in my name. And when I found out those gems were counterfeit, I felt unmoored, angry, and betrayed. There is so much secrecy in adoption, and though some may say that my parents meant well in trying to paint over the difficult parts of my story, they did not protect me by hiding the truth. Instead, they made clear that I must carry it alone.

I never told my parents what I discovered in my file. Our family does not talk about tough topics. Instead, we tuck them up on high shelves. My parents and I have a distant relationship for all kinds of complicated reasons, but their failure to preserve my history is emblematic of our challenges.

Be Genuine, Honest, Open

Adoptive parents must honor their child’s story, and remember that to an adoptee, our birth family is always our forever family. Our heritage, country of birth, ancestors, birth parents, and life before we were adopted must be honored by our adoptive family, through genuine, honest, and open conversation. Adoptive parents should know their child’s story as accurately as if they lived it with them. They should make their child’s file available in an age appropriate way, and no child should be left straining on their tiptoes to access their own history. When I think about the small me, straining to reach that binder, so scared she is doing something wrong, I wish she had a parent to hold her, to tell her she can stop hiding, and to dive into her complicated and essential history together. I wish she did not feel so alone.

About Cynthia Landesberg

Born in Busan, South Korea, and adopted by Jewish parents, Cynthia Landesberg grew up in the suburbs of Washington, DC, where she still resides. She is a mother, lawyer, and writer. You can find more of her writing in The Washington Post, Witness, and on her website, www.adoptionsquared.com.

- Website: AdoptionSquared.com

- Links to published works

Adoptees on Adoption 2022

- Love With A Big Love by Danielle Gaudette

- What I Wish You Had Known While Raising Me by Emma Stevens

- The Green Binder by Cynthia Landesberg

- A Simple Question with Many Answers by Rebecca Cheek

- Happy Birthday by Roberta Holland

- Don’t You Know We Love You? by Lorah Gerald

- Why My Truth Matters More Than Your Comfort by Brad Ewell

- Being Open is the Right Path by Allison Olson

- Adoptees on Adoption 2022 entire series

- Adoptees #flipthescript 2014-2016

Lori Holden, mom of a young adult daughter and a young adult son, writes from Denver. She was honored as an Angel in Adoption® by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute.

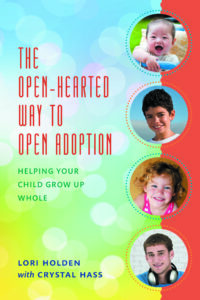

Her first book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, makes a thoughtful anytime gift for the adoptive families in your life. Her second book, Standing Room Only: How to Be THAT Yoga Teacher is now available in paperback, and her third book, Adoption Unfiltered, is now available through your favorite bookseller!

Find Lori’s books on her Amazon Author page and catch episodes of Adoption: The Long View wherever you get your podcasts.

6 Responses

I always wonder about this with my nieces. I think I asked them a couple years ago if they would want to try to trace their roots in China, they both said no. I hope they know that I (and probably my sisters, but I am not 100% sure) would support that endeavor.

I’m wondering this: what is behind their saying no to wanting to trace their roots? Perhaps they truly never had any curiosity about that, but from what I hear from so many adoptees, that desire is innate, and to not have it means it got quashed somewhere along the way.

My A-parents had a box. I searched through it when they were at work, also carefully covering my tracks. I found out my last name! I kept it to myself.

It’s sad that something so personal and important to you was kept from you.

As an adoptee, I strongly felt Cynthia’s words. It made me reflect on my own internal struggle to find my truth and be told my truth didn’t belong to me. It’s like adoptees are told it’s wrong to even want to know — but the message so many of us received, or internalized, was that who we are is wrong.

How was it that such an unintended message — that who one IS is wrong — was not anticipated in the practice of keeping truth from people out of manufactured shame and harmful secrecy?