Jess simultaneously straddles two sides of The Adoption Wait — waiting to get picked as adoptive parents and waiting to be matched as embryo donors (there’s a new development on that on her blog).

In this guest post about her ridiculously crazy journey through infertility, third party reproduction, and adoption, Jess tells how her beliefs evolved from conventional wisdom (let’s not worry about those pesky genetic origins) to a viewpoint that’s perhaps more informed and empathetic.

Jess: When Bryce and I started our family building journey, openness wasn’t even a term on our radar. We’d do some IUIs, hope for the best, and if necessary, move on to recommended IVF cycles that would surely overcome our combined issues of PCOS and male-factor infertility.

That’s not quite the way things worked out.

After three years of unsuccessful treatment including IVF cycles, an ectopic pregnancy, and a miscarriage, we couldn’t put a finger on why we were still babyless. Our clinic recommended we explore donor egg, as I was now 36, the dreaded “advanced maternal age.”

I was sad to give up my genetics, but if it meant I could be pregnant and give birth to our baby? Sign me up.

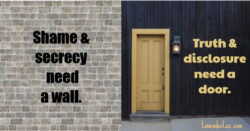

Anonymous = Neat and Tidy

Our clinic had its own donor bank, managed as an anonymous program. This seemed fine to me — this donor person was a special ingredient, someone who would provide the necessary material so that I could manifest this baby, and through epigenetics even influence the genes just by carrying it. The donor’s contribution would be amazing, but still, a simple contribution. I would have a sheet of paper to present to our child, whom we were intending to tell from the beginning, of his or her origins through egg donor. We’d be able to share hair color, interests, and other minimal biographical information.

I didn’t think at the time, but what if my child wants to know more? What if they are curious about heritage, if they look more like her than like me, if there are other personality traits that might come from genetics?

It seemed neat and tidy enough the way it was handled. Special ingredient and not much else, anonymous to protect everyone’s privacy, a generous gift given by a faceless young woman who was compensated for her time and sizeable medical effort and went into the process eyes wide open, sharing just enough information to quell future curiosity and ensure a good match.

During this time I read an article from an egg donor on how it felt to have shared her genetics and then have no idea what happened to the resulting children, to wonder when traveling if a child who resembled her in any way was indeed part of her genetic legacy, and how wonderful it would have been if the option of letters and pictures had been available to her.

I felt uncomfortable; I hadn’t thought about that side of things. But then I thought, they sign a contract, they know what they’re entering into, of course you might wonder “what if” later, but anonymity means that’s that. I pushed her perspective into the periphery of my subconscious.

Donor Sperm: A Whole Different Ballgame

Meanwhile, our egg donor cycles didn’t work. We had multiple second opinion consults and switched to a new clinic and everyone seemed to think maybe it’s the sperm.

So my eggs were back on the table, and we were now looking at obtaining donor sperm. Which turned out to be a very, very different experience.

Instead of an anonymous program through the clinic, donated sperm was handled through a cryobank, and the sheer amount of information available was dizzying. We paid for the biggest subscription, because we wanted to make our decision based on as much info as possible and have that information for our child. (It did feel odd that more money got you more information.) It was incredible that we had basic biographical and biological information, but now we also had a voice interview, childhood pictures, an extended family history and autobiography. SO much information.

It made my single sheet for the egg donor look incredibly sparse. And a little sad.

We chose as our donor a gentleman who had eerie similarities to Bryce and also was classified as an “open” donor — not anonymous, and willing to meet with our child at 18 once to discuss any questions he/she might have.

WELL. The disparity between the two processes made our minds whirr and click.

Openness = Not So Scary After All

We still had six embryos from the egg donor. What if we conceived a child from the sperm donor, and ALSO from the egg donor? How could we explain to any resulting children this complete and total inequity of information available? Oh, Archie, we have pages and pages and audio files on your special ingredient, but sorry Betty, you get just an impersonal one-page form to connect with. Hope that answers your questions.

I started seeing that perhaps openness wasn’t so scary, that it was a way to connect the dots, to satisfy a hunger for self-information. It bothered me that we had so much more from one donor source and so much less from the other. I began to see more from the viewpoint of my child, who might wonder about the person who made their existence possible, a piece of their history.

(I also briefly thought of family tree projects and high school biology punnett square activities that would leave my future child confused and the teachers probably more so.)

Strike Three, We’re Out

We were left without having to thoroughly resolve the issue of disparity in donor information because the sperm-donor embryos didn’t work either. It seemed more and more that the true culprit was my uterus, the only variable we didn’t replace in our efforts to conceive and carry. We made the devastating decision to end treatments, our frozen embryos still in our care without a place to land.

We put our embryos on ice for a year of storage and waited to make a decision. We dove head first into the world of domestic infant adoption through a non-profit agency, getting a whole new introduction to the concept of openness.

I started researching open adoption and exploring the many perspectives on embracing openness. My agency encourages openness, and our homestudy classes involved talking with adoptees, a birth mother, and an adoptive mother about the realities of open adoption. The agency recommended many books, like Lori Holden’s The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption, which also covers openness with donor gametes. It recommends her blog, as well, the one you’re reading now. I appreciate how her space explores the concept and spirit of openness within the adoption constellation from all sides, and that it doesn’t lead me to believe open adoption is an easy way.

My research confirmed what I’d begun to suspect when we started looking into donor eggs and sperm– that openness would be advantageous to a resulting child and thus to us.

A Weird Double Wait

Before we knew it, our storage time came to an end. We found ourselves going through our adoption homestudy and beginning our wait in earnest, while simultaneously researching the world of embryo adoption– as placing parents.

What a strange circumstance — to be waiting for a match with an expectant mother who will embrace openness, and then to also take our remaining 8 embryos (6 from the egg donor and 2 from the sperm donor) and donate them to another couple to gestate and raise in their family.

We chose Snowflakes because it gave us the option to choose where the embryos go, to know what happens to them, and to have a small window into the lives of the children who may result from the biggest of team efforts. We don’t align philosophically with Snowflakes on all matters (cough, personhood, cough cough), but it didn’t matter because they work tirelessly to find a match for every embryo, for their own reasons, while we hope to give our specific embryos, created from a desire to become parents, something we couldn’t offer them…the chance to be.

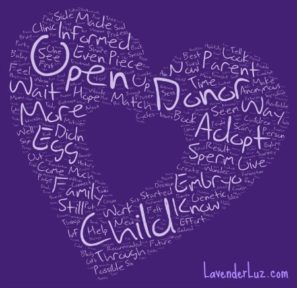

So now our idea of openness goes in every possible direction — we hope for an open adoption where our child can have all of his or her pieces available in whatever way is possible. We wait to have our embryos matched with a family who will also subscribe to openness and give us a way to be openly connected to future children who aren’t ours to parent, but whom we made possible through our efforts to have a baby.

Upon viewing our first profile book from a couple seeking to adopt embryos, we discovered that openness can be scary to people who are entering into third party reproduction. It helps looking back on our own journey that it was a frightening notion, a feeling of, but what if then I’m not seen as the REAL parent? It’s helpful to remember that with education and information, our stance evolved to I will be legit in my parenting, and I no longer need to negate my child’s connection to her genetic parents to resolve my feelings of insecurity. I can’t pretend that we are the only players in this game, and our child deserves to know about all pieces of herself.

The profile book stated that semi-open to closed is best for the family, offering “some or no contact at all if preferred.” We told our story through an intermediary and expressed our concerns about closedness. We hope that in understanding what brought us to embryo donorship, the receiving family will see why we consider openness so valuable.

From Subtraction to Addition

I can see why openness is scary at first. It felt as though acknowledging the other parents required me to relinquish a bit of my role, diminishing my own importance.

Now I can see that it isn’t relinquishing at all. It’s not giving up something — it’s an inclusion of more. That providing for my child the chance to know all parts of her heritage and history doesn’t mean choosing the other parents over me. That all of the pieces, the nature and the nurture, come together to create a whole person. And that is the greatest gift I can give any child who results from any of the processes we are engaged in — the children from the frozen embryos that hopefully come to be, the child we adopt hopefully sooner than later — a sense of who they are, where they come from, what pieces all commingled and swirled about to create the gloriousness of their existence. Even when that existence comes about due to SIX people, as will be the case with the frozen embryos, should a child result from both sets.

Reframing the concept of openness has helped me to wrap my head around the presence of others in our future child’s story. Though openness won’t always be easy, we know it’s beneficial for all involved, especially for the child. With openness, he/she need never feel betrayed by a secret, and can know about their pieces even if some information or contact isn’t available. Openness may make things seem murky at times, but we will do the best we can with this grafted, twisty family tree we are trying so hard to grow, and hope that the branches cultivated by so many people flourish.

Jess, a middle school special education teacher, is surviving the adoption wait by writing, gardening, and cooking tasty gluten-free food. She has been writing about her infertility and adoption journey for nearly six years at My Path to Mommyhood, which was a RESOLVE Hope Award Best Blog Nominee in 2012. Jess and her husband Bryce live in Western NY with their two cats and the hope that one day a real live baby will enjoy the nursery as much as the furry ones do.

4 Responses

Yay for this interview!!!! Yay, yay, yay!!!

Thanks, Cristy! It’s been an education I never thought I would have needed, but I hope in sharing my story and perspective it might help other people to consider (or reconsider) the concept of openness.

This is fabulous! Jess has such a unique perspective. I’m so pleased that the issues of openness around embryo, sperm, and egg donation as well as in adoption are being discussed by such wise and honest people.

Thanks, Mali–I’d say unique is pretty accurate. Thank you for your kind words as we navigate all these ways to be open!