How easily can a proud parent’s enthusiastic sharing become oversharenting? Sara Easterly is back to help adoptive parents remember to see even the most common things from our child’s point of view.

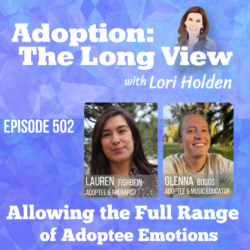

Aside: my interview with Sara for the podcast Adoption: The Long View was just released! It kicks off National Adoption Awareness Month, which centers on marginalized voices — adoptees and birth parents.. Make sure to subscribe wherever you get your podcasts (here’s where I do).

Sara’s episode is sooooooooo good and juicy — all of the episodes are!

Deciding when and how to share our kids’ stories publicly can be tricky for parents to navigate, especially when it seems everyone around us is posting photos and stories of their children online. Kid-focused posts are usually met with adoration from mainstream culture, who cherish a refreshing break from the rest of the feed that is so often ranting, despairing, or arguing.

Understandably, parents through adoption would like to be able to share their parenting joys online, too. Such sharing is rampant, as a tour through the thousands of posts tagged #adoptionrocks reveals.

But from an adoptee’s perspective, there are important dynamics to be mindful of before publicizing adoption-related stories. Here are eight of them:

1. Consent and oversharenting

Young children are unable to provide consent around whether their pictures and stories are shown on the Internet or in other public spaces. But for adoptees, consent is even more complicated than age.

There’s a power imbalance inherent in all mother-child relationships—needed, of course, to parent our children—but we must treat that power with care, especially when it comes to seeking consent from adoptees.

Adoptees are not able to provide true consent to the sharing of their adoption stories until they are “out of the fog”—able to walk their way around all sides of adoption and put into their own words what it means to them. Until then, they will be too worried about pleasing their parents to make authentic decisions around consent.

As an adoptee, I write from experience. Sadly, I was unable to speak my truth around this to my adoptive family until I was in my 40s and my adoptive mother had died. Until then, I spent years politely nodding along as she used my story to sing the praises of adoption.

I’d learned at a very early age how to read others and be “good” for my parents—particularly my adoptive mom. From my brain’s perspective, my first mother abandoned me, so I learned to comply in order to keep my next mother close. I desperately needed to win her love. To my survivalist brain, it was a matter of life or death. There was no way I could be honest with my mom about how much it hurt each time she shared “our” adoption story with others.

2. Silencing adoptees

When adoptive parents lead the conversation on adoption, it silences adoptees and reinforces flawed beliefs.

Unfortunately, my mom’s adoption story was not really “our” story. My story was a different one. And each time my mom shared her story, she unknowingly pushed my story to the background—so much so, that there was no space for me to make sense of it.

Even though I landed in a wonderful adoptive family, because of the initial relinquishment and loss that’s inherent in adoption, I lived prone to feeling like I didn’t matter. The continual sharing of my mother’s side of the story only seemed to reinforce this flawed belief.

3. Control is very important to adoptees

From the moment it’s determined that we’re better off in one family over another, our destinies, and often our lives, feel beyond our control.

We try to make up for this lacking sense of control in any number of ways. For me it was creating handwritten spreadsheets cataloguing all of my stuffies, and as an adult, going into event planning, where I could control thousands of logistical details. For other adoptees, it might be control over relationships, or eating, or varying forms of self-attack.

No matter how it manifests in adoptees’ lives, when we’re blatantly not in control, it can trigger unhealthy ways of seeking control. More than anything, we should have complete control of our personal stories—including how, and when, we wish to share them.

4. Adoptees are sensitive to feeling used

Whenever family preservation is bypassed in favor of adoption, an adoptee is used to complete another family. This is the setup of adoption—no matter how great the need for the adoption, and regardless of the loving environments in our adoptive families. Even if it’s hard to agree with this logic, it’s important to be aware of this dynamic and tread gently around it.

Adoptees don’t want to be used by our parents in the name of platform-building or garnering likes. We don’t want to be used to prop up adoption, advocate against abortion, or, in the case of transracial adoption, demonstrate a parent’s racial wokeness.

5. Perpetuating adoption myths

#adoptionrocks and phrases like “forever family” perpetuate myths.

When it comes to adoption, everything is more complex than simple hashtags or catchy phrases convey. And more often than not, delighted adoptive parents tend to perpetuate the myth that adoption is an entirely beautiful and noble thing.

Adoption can certainly be beautiful—mine was. But it was hard, too, and filled with pain that I felt alone in and overwhelmed by because the myths squeezed out room for complexity.

Without the nuances and perspectives of adoptees—whose bodies carry the complete range of emotions and experiences tied to adoption—the #adoptionrocks myth is not only superficial but causes harm.

Myths don’t help other families when they encounter struggles. Presenting one-sided, sunny stories of adoption are harmful to adoptees, who suffer in isolation and are four times more likely to attempt suicide. Superficial depictions of adoption, too, can cast shadows on our closest relationships.

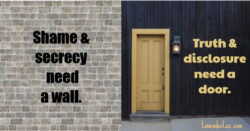

6. Trust and honor are sidelined

There is a level of mistrust in the parent who publicly shares, because their child’s story has not been honored.

Attaching deeply is already risky for adoptees, due to the trauma of relinquishment. That fragile parent-child relationship becomes even riskier when parents center themselves in stories that ultimately belong to their children. The child’s defended heart asks: Can my mom really be trusted? Does my parent really see and know all parts of me?

Our goal in parenting is for our children to feel safe enough to depend on us. We need that dependence in order to lead children. An environment of trust and safety is also critically important for helping our children to learn to love deeply—paramount to emotional wellness.

7. Setting up adoptees for relational problems

Sharing adoptees’ stories sets up adoptees for relational problems.

If a child learns to be compliant and adapt to their parents’ needs for sharing a child’s stories, how will that same child stand up for themselves in adolescence? Or in a romantic setting when feeling pressured? Or in a work setting when asking for a well-deserved raise?

Having our privacy constantly violated teaches adoptees that consent means consenting. We infer that our purpose as adoptees is to meet others’ needs.

Unintended outcomes: We may not understand healthy boundaries, how to advocate for ourselves, or where all of our immense frustration comes from that catches us all by surprise when it comes out as a storm.

8. Adoptees need room to evolve

Adoptees will evolve and change their views on adoption as time goes on.

Even though my own children are not adopted, I obtain their consent before sharing stories about them online or in other public spaces. But I still have to ask myself if it that consent will hold as their levels of consciousness and critical thinking evolve.

For adoptees, our understanding of adoption is guaranteed to shift over time. As decades press on and maturity informs, our feelings change. I wasn’t able to look honestly at the impact of my adoption until mid-life. Only then could I articulate some of the discomfort or irritation I’d previously felt when consent was sought. While I’d politely given it then, I wouldn’t do so now.

Keeping the decades-long evolution in mind is a good reminder to err on the side of caution when it comes to publicly sharing.

In Summary, Proceed with Awareness

In this social media age, most of us have made mistakes in this area. I’m an excited and proud parent who’s guilty of oversharenting about my kids, too.

But awareness of the dynamics around the sharing of adoptees’ stories, and holding an honoring and sensitive perspective before going public, will make an important difference for adoptees and their parent-child relationships.

Sara Easterly is the author of Searching for Mom: A Memoir, a gold medal winner of the Illumination Book Awards. Her essays and articles have been published by Dear Adoption, Psychology Today, Feminine Collective, Her View From Home, Godspace, Neufeld Institute, and the Society of Children’s Book Writers & Illustrators (SCBWI).

Sara is mom to two tenacious daughters and daughter of two amazing moms—both her adoptive mom and her birth mother. She enjoys supporting mothers in their journeys and has a passion for helping the non-adopted better understand the hearts of adopted children. Find her online at www.saraeasterly.com.

Remember to tune in for more Sara on Adoption: The Long View during November, National Adoption Awareness Month. I suggest seeking out adoptee and birth parent voices as the “awareness” part.

Along These Lines

- Where is the Oversharing Line in Our Adoption Stories?

- Pour it through the Oversharenting Sieve before you post

- Michigan State University on oversharenting for all parents (not just adoptive parents)

- More guests posts from Sara Easterly

Lori Holden, mom of a young adult daughter and a young adult son, writes from Denver. She was honored as an Angel in Adoption® by the Congressional Coalition on Adoption Institute.

Her first book, The Open-Hearted Way to Open Adoption: Helping Your Child Grow Up Whole, makes a thoughtful anytime gift for the adoptive families in your life. Her second book, Standing Room Only: How to Be THAT Yoga Teacher is now available in paperback, and her third book, Adoption Unfiltered, is now available through your favorite bookseller!

Find Lori’s books on her Amazon Author page and catch episodes of Adoption: The Long View wherever you get your podcasts.

5 Responses

This well-written post shares some important, hard truths. Thanks for sharing.

Your viewpoint means a lot to me. I’m a birth-mom and my birth-daughter has a lot of anger toward me and has cut all ties. Ours was an open adoption. I made the mistake of sending her a letter, written over her lifetime, on her 21st birthday. I failed to think of her needs. I only wanted to tell her what I had been feeling all those years. Her parents stopped sharing her life with me at about age 10. It was hard because I didn’t understand why and assumed it was something I had done. I love her parents very much. I chose them when I was 4-months pregnant and we became close over the pregnancy, birth, and ten years following. I want to know her pain, why this love became animosity. I will always love her, but perhaps it will hurt less if I understand more. Thank you for writing this article. With smiles, ♥. Niki

I’m so sorry your daughter’s parents didn’t continue sharing her life with you. I can certainly understand why that would cause a tremendous amount of pain. Do you have someone to help you work through these big emotions?

May you and your daughter find your way to each other somehow, some way. May you find that understanding you seek. Keep me posted. I care.

Lori, I’m sorry I only today saw your response to my comment. I really appreciate what you wrote. I had a therapist but she’s moved to admin and no longer sees clients. So I’m hoping to find someone else I like as much. Thanks for asking. I hope we do find our way back to each other. ♥.

This is such an important read. Thank you for highlighting Sara Easterly. Also, I love the term “oversharenting!”